New York Times, New York, New York, Monday, August 09, 1971 - Page 31

Fischer Munches a Bagel and Finds 11 Chess Rivals a Piece of Cake By Paul L. Montgomery

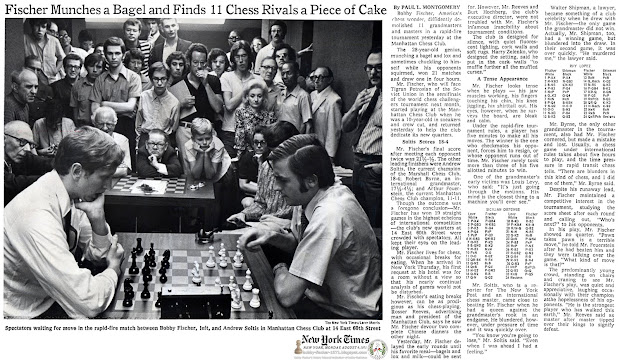

Bobby Fischer, America's chess wonder, diffidently demolished 11 grand masters and masters in a rapid-fire tournament yesterday at the Manhattan Chess Club.

The 28-year-old genius, munching a bagel and lox and sometimes chuckling to himself while his opponents squirmed, won 21 matches and drew one in four hours.

Mr. Fischer, who will face Tigran Petrosian of the Soviet Union in the semifinals of the world chess challengers tournament next month, started playing at the Manhattan Chess Club when he was a 10-year-old in sneakers and crew cut, and returned yesterday to help the club dedicate its new quarters.

Soltis Scores 18-4 Mr. Fischer's final score after meeting each opponent twice was 21½-½. The other leading finishers were Andrew Soltis, the current champion of the Marshall Chess Club, 18-4; Robert Byrne, an international grandmaster, 17½-4½; and Arthur Feuerstein, the current Manhattan Chess Club champion, 11-11.

Though the outcome was a foregone conclusion—Mr. Fischer has won 19 straight games in the highest echelons of international competition — the club's new quarters at 14 East 60th Street were crowded with spectators. All kept their eyes on the leading player.

Mr. Fischer lives for chess, with occasional breaks for eating. When he arrived in New York Thursday, his first request at his hotel was for a room without a view so that his nearly continual analysis of games would not be disturbed.

Mr. Fischer's eating breaks however, can be as prodigious as his chess-playing. Rosser Reeves, advertising man and president of the Manhattan Club, says he saw Mr. Fischer devour two complete Chinese dinners the other night.

Yesterday, Mr. Fischer delayed the early rounds until his favorite meal—bagels and lox and milk—could be sent for. However, Mr. Reeves and Burt Hochberg, the club's executive director, were not troubled with Mr. Fischer's infamous irascibility about tournament conditions.

The club is designed for silence, with quiet fluorescent lighting, cork walls and soft rugs. Harry Zelenko, who designed the setting, said he put in the cork walls “to muffle further all the muffled curses.”

A Tense Appearance Mr. Fischer looks tense when he plays — his jaw muscles working, his fingers touching his chin, his knee jiggling, his shirttail out. His eyes, however, when he surveys the board, are bleak and calm.

Under the rapid-fire tournament rules, a player has five minutes to make all his moves. The winner is the one who checkmates his opponent, forces him to resign, or whose opponent runs out of time. Mr. Fischer rarely took more than three of his five allotted minutes to win.

One of the grand master's early victims was Louis Levy, who said: “It's just going through the motions. His mind is the closest thing to a machine you'll ever see.”

Mr. Soltis, who is a reporter for The New York Post and an international chess master, came close to beating Mr. Fischer when he had a queen against the grand master's rook in an endgame. He blundered, however, under pressure of time and it was quickly over.

“You know you're going to lose,” Mr. Soltis said. “Even when I was ahead I had a feeling.”

Walter Shipman, a lawyer, became something of a club celebrity when he drew with Mr. Fischer—the only game the grandmaster did not win. Actually, Mr. Shipman, too, had a winning game, but blundered into the draw. In their second game, it was over quickly. “He murdered me,” the lawyer said.

Mr. Byrne, the only other grandmaster in the tournament, also had Mr. Fischer cornered, but made a mistake and lost. Usually, a chess game under international rules takes about five hours to play, and the time pressure in rapid transit chess tells. “There are blunders in this kind of chess, and I did one of them,” Mr. Byrne said.

Despite his runaway lead, Mr. Fischer maintained a competitive interest in the tournament, studying the score sheet after each round and calling out, “Who's next?” to his opponents.

In his play, Mr. Fischer showed no quarter. “Pawn takes pawn is a terrible move,” he told Mr. Feuerstein after he had beaten him and they were talking over the game. “What kind of move is that?”

The predominantly young crowd, standing on chairs and craning to see Mr. Fischer's play, was quiet and appreciative, laughing occasionally with their champion at the hopelessness of his opponents. “He is the strongest player who has walked this earth,” Mr. Reeves said as master after master tipped over their kings to signify defeat.