The Los Angeles Times Los Angeles, California Sunday, August 15, 1971 - Page 43

Bobby Fischer: Chess Is His Life

'His Mind Is the Closest Thing to a Machine You'll Ever See . . . When I Was Ahead I Knew I Was Going to Lose,' Say Opponents. By Ross Newhan, Times Staff Writer

New York—The other day, during a lunch of lox and bagels at the Manhattan Chess Club, Bobby Fischer quickly demolished 11 masters and grandmasters of the science.

His opponents were mere pawns.

“He was just going through the motions,” said one of Fischer's foes. “His mind is the closest thing to a machine you'll ever see.”

“You know you're going to lose,”

Bobby Fischer first played at the Manhattan Chess Club when he was 10 years old. He will be remembered as the prodigy who won the United States championship at the age of 14.

Now 28, he has since won eight U.S. titles. He has won 19 straight matches from the game's highest ranking players, including a recent 6-0 humiliation of grandmaster Mark Taimanov.

Fischer is preparing to meet Tigran Petrosian of the Soviet Union in the semifinals of the world challengers tournament next month.

A victory will send him against Boris Spassky, holder of the world title, a crown that has eluded Fischer, who describes the Russians as blatant cheaters.

Fischer's bid to win the world title is a crusade. Chess is his life, his passion.

He is described as a genius and his fringe traits are characteristic.

His days, he admits, are disorganized. He does not walk, he runs. He is incessantly jiggling his leg or tapping his foot as he talks.

He goes to bed at 5 in the morning and gets up in the afternoon. Groping to pay a bill, he cannot remember in which pocket he put his money.

He complains about noise while he is playing and he complains about noise while he is being interviewed. Checking into his hotel here, he requested a room without a view so he could concentrate.

Girls, he says, are not interested in him. His clothes are late Goodwill: a soiled blue suit with narrow lapels and cuffs on the pants, a white shirt and thin blue tie.

He reads: the newsmagazines, books on chess, a Russian newspaper that features chess. He is intrigued by a personality like Joe Namath. But he does not like football because of the brutality and he does not like baseball because it is slow, a strange statement from a man who often spends five hours over one game of chess.

He says he played the street games, stickball and dodge ball, while growing up in Brooklyn, but at an early age he asked his mother which was the hardest game.

“When she said it was chess,” said Fischer, ”then that was the game I wanted to play I don't think it was unusual. It was just the way I was.

“The other kids couldn't chide me about it because I was already better than they were in their games . . . like stickball and dodge ball.”

If it was the way he was, it is the way he remains.

“Chess isn't that popular in this country because people don't want to think that much,” said Fischer. “I see some hope in today's youngest people, but the older ones won't change. They just want to be entertained.”

The executive director of the U.S. Chess Federation was talking about Bobby Fischer.

“It can definitely be said,” stated E.B. Edmondson, by telephoned from his home in Ventura, “that Bobby is the greatest chess player in the world.

“The simple fact is that he is a genius and as such he doesn't conform to what is the thought process for most of us.

“He is a young man bursting with energy. A walk to the corner is not just a walk to the corner, it's an energetic experience.”

Please Turn to Page 9, Column 1.

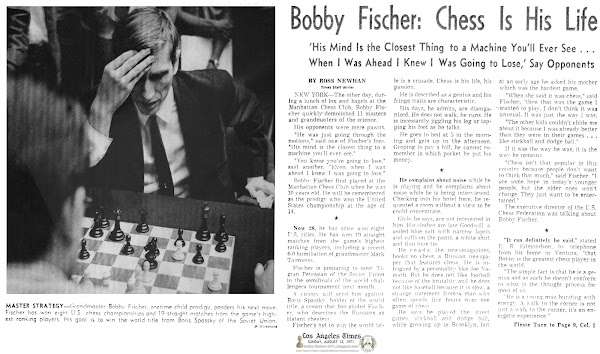

Caption: Master Strategy—Grandmaster Bobby Fischer, onetime child prodigy, ponders his next move. Fischer has won eight U.S. chess championships and 19 straight matches from the game's highest ranking players. His goal is to win the world title from Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union.

The Los Angeles Times Los Angeles, California Sunday, August 15, 1971 - Page 51

Continued from First Page

Edmondson has known Fischer for nine years.

“Bobby is absorbed with chess,” he said, “but that's no different than any genius in any form — Bach when he was composing, Michelangelo when he was painting.

“But Bobby is deceptive, too, and only those people who know him well are aware that he has other interests. He likes popular music. He follows the developments in the electronics industries. He is aware of national and world affairs.”

In his bid for the world championship, the USCF is supporting Fischer through its charitable trust, a tax deductible program.

“We're supporting Bobby,” said Edmondson, “because if he were to win, it would be good for chess and good for the country as a whole.

“It would offset the propaganda the Russians make out of the chess championships they hold.

“The underdeveloped countries would understand the meaning of a young man on his own beating state-supported players. It would be additional evidence in support of the superiority of our system.”

The interview on the day after Fischer's appearance at the Manhattan Chess Club is set for 3 p.m., an hour after he awakens.

Fischer at the moment is a man without a home and the meeting is in the lobby of a midtown Manhattan hotel where he is staying.

For lunch, he suggests the Automat, taking into consideration either his own budget or the writer's expense account.

The walk of four blocks is a frenzied dash on which a slow starter like Dr. Delano Meriweather never would have caught up.

At the Automat, Fischer chooses two pieces of watermelon and three glasses of tomato juice.

He finds a table in the heart of an area where a man is mopping the floor, and he does not pardon himself as he first browses through the newspapers, checking to see if there were any stories on his performance at the Chess Club.

He lifts his head and asks:

“Is this going to be a big story you're doing?”

“Depends on you,” he is told.

“I want a copy of it,” he says.

He is asked if chess belongs on the sports page.

“Yes, if I were an editor that's where I would put it.

“Chess is a science, but it's basically a sport.”

Fischer explained that when he is in training for a match as important as the one he is in training for now, he must reach a physical as well as mental peak.

“During a tournament,” he said, “I'll play five-hour matches six days a week. That takes stamina.

“I swim, walk, play tennis or even bowl.”

But he does none of it regularly.

“My life is disorganized,” he said. “I don't know what I'm going to do tonight or tomorrow.”

Generally, after arising in mid-afternoon, he has something to eat, walks, reads or plays chess for awhile, has something to eat, walks, reads or play chess for awhile, has something to eat, returns to his hotel room, reads and then retires just before the city awakens.

“It's quiet and I find that I can concentrate better after midnight,” he said. “I also need a lot of sleep, and that's why I don't get up until the afternoon.”

Fischer does not play a great deal of chess when preparing for an important match.

“I don't want to tire myself out,” he explained.

He laughed when he was asked if he is truly a genius.

“It's a word. What does it really mean?” he asked. “If I win, I'm a genius. If I don't, I'm not.”

He did not laugh when the Russians were mentioned. His match with Petrosian will be held in Argentina, France, Greece or Yugoslavia. Fischer said he will not play in Russia and suspects that Petrosian will not play in the United States.

”In Russia,” he said, “they would do everything they could to distract me.

“They'll try to win any way they can. They have no sense of sportsmanship. They find ways to take advice from their seconds or they arrange the schedule against you as they did to me in the finals of the 1962 world tournament.

“I don't feel I was cheated: I know I was. They know they're cheaters and they respect me for saying it.

“The Russian players are simply employees of the state. They have no personalities. They don't think for themselves.”

As employees of the state, they may earn more money than Fischer, who receives some subsidy from the United States Chess Federation, but chooses not to divulge his earnings over the years.

“Relatively,” he said, “the tournament prizes are very small. It's unfortunate, because I play better when money is involved.

“The world championship is worth only $2,000, but it would open up several things . . . lectures, title matches, endorsements.”

Charlotte Saikowski of the Christian Science Monitor reported from Moscow the other day that the Fischer-Petrosian match is the talk of the Russian capital. Said one enthusiast there:

“Fischer will win.”

“Why?” he was asked.

“Because he's an offensive player. He'll take risks. Petrosian's style is defensive.”

Spassky, the world champion, is reported to have remarked that Fischer always plays a strong game but that Petrosian is stronger.

“Not having encountered strong opposition, the American grandmaster naturally could not receive the proper training as a chess player,” Spassky is quoted as saying in a press account. Sooner or later, Fischer will begin meeting with unpleasantness, and it is not yet known how he will conduct himself in such a situation.”

Fischer and Petrosian have played each other 18 times since 1958. The score is three victories each and 12 ties.

Should Fischer get by Petrosian and then defeat Spassky, he would be the first non-Soviet champion since 1948.

Fischer appeared last week on the Dick Cavett television show, but the United States' greatest chess player lives in relative anonymity.

“If I've received a lot of publicity in a local newspaper, a few people might recognize me on the street,” he said, “But I'm not like a Namath.

“The lack of recognition doesn't bother me. I have too many other things to think about.”

Fischer did not attend college, nor did he graduate from Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. His mother fostered his interest in chess and he has since majored in the subject.

“A championship match is like a five-hour examination,” he said.

Fischer has 12 times traveled abroad to study at the chess centers of Europe and he is constantly reading new books on the subject. He calls Isaac Kashdan, The Times chess writer, the best in the country.

Fischer, who often laughs sardonically whenever he has his foe sweating, said of Spassky, the world champion, “He's not that tough. I expect to beat him.”

Fischer finished his last piece of watermelon, raised his feet so the man could mop under them, and said:

“Chess is my life. Yes, it's my life.”