The Province Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Friday, May 21, 1971 - Page 46

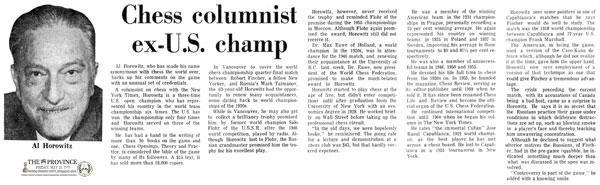

Chess Columnist Ex-U.S. Champ

Al Horowitz, who has made his name synonymous with chess the world over, backs up his comments on the game with an unusual set of credentials.

A columnist on chess with the New York Times, Horowitz is a three-time U.S. open champion who has represented his country in the world team championship six times. The U.S. has won the championship only four times and Horowitz served on three of the winning teams.

He has had a hand in the writing of more than 30 books on the game and one, Chess Openings, Theory and Practice, is considered the bible of the game by many of its followers. A $15 text, it has sold more than 18,000 copies.

In Vancouver, to cover the world chess championship quarter-final match between Robert Fischer, a fellow New Yorker, and Russia's Mark Taimanov, the 63-year-old Horowitz had the opportunity to renew many acquaintances, some dating back to world championships of the 1930s.

While in Vancouver, he may also get to collect a brilliancy trophy promised him by former world champion Salo Flohr of the U.S.S.R. after the 1946 world competition, played by radio. Although Horowitz lost to Flohr, the Russian grandmaster promised him the trophy for his excellent play.

Horowitz, however, never received the trophy and reminded Flohr of the promise during the 1955 championships in Moscow. Although Flohr again promised the award, Horowitz still did not receive it.

Dr. Max Euwe of Holland, a world champion in the 1920s, was in attendance for the 1946 match, and, renewing their acquaintance at the University of B.C. last week, Dr. Euwe, now president of the World Chess Federation, promised to make the much-belated award to Horowitz.

Horowitz started to play chess at the age of five, but didn't enter competitions until after graduation from the University of New York with an economics degree in 1928. He worked briefly on Wall Street before taking up the professional chess circuit.

“In the old days, we were hopelessly broke,” he reminisced. The going rate for a lecture and demonstration at a chess club was $45, but that hardly covered expenses.

He was a member of the winning American team in the 1931 championships in Prague, personally recording a 70 per cent winning average. He again represented his country on winning teams in 1935 in Poland and 1937 in Sweden, improving his average in those tournaments to 80 and 87½ per cent respectively.

He was also a member of unsuccessful teams in 1946, 1950 and 1955.

He devoted his life full time to chess from the 1930s on. In 1933, he founded the magazine, Chess Review, serving as its editor-publisher until 1969 when he sold it. It has since been renamed Chess Life and Review and become the official organ of the U.S. Chess Federation.

He continued international competition until 1960 when he began his column in The New York Times.

He rates “the immortal Cuban” Jose Raoul Capablanca, 1921 world champion, as the best player he has met across a chess board. He lost to Capablanca in a 1931 tournament in New York.

Horowitz sees some pointers in one of Capablanca's matches that he says Fischer would do well to study. The match was the 1918 world championship between Capablanca and 27-year U.S. champion Frank Marshall.

The American, in losing the game, used a version of the Caro-Kann defense which, although he did not realize it at the time, gave him the upper hand. Horowitz now seems employment of a version of that technique as one that could give Fischer a tremendous advantage.

The crisis preceding the current match, with its accusations of Canada being a bad host, came as a surprise to Horowitz. He says it is no secret that the Russians practice their game under conditions in which deliberate distractions are set up, such as blowing smoke in a player's face and thereby teaching him unwavering concentration.

Although he declined to suggest what ulterior motives the Russians, of Fischer, had in the pre-game squabble, he indicated something much deeper than what was discussed in the open was involved.

“Controversy is part of the game,” he added with a knowing smile.