New York Times, New York, New York, Sunday, June 06, 1971 - Page 188

Chess - While the Challengers Battle by Al Horowitz

While the eight Candidates are struggling fiercely in matches to determine who will be his next challenger, world champion Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union waits calmly in the wings. His entrance into the great drama won't come until the spring of 1972, far enough so that his preparations need not yet have swung into high gear.

How then does the world champion pass the time? Well, he is reported to be an enthusiastic bridge player, and has been known to tip his hat to a passing lady on occasion. But there can be little doubt that he does play over the games of the Candidates' matches as they are reported in the press, and he may well be inclined to glance now and again at some book in his chess library—like Bobby Fischer's “My Sixty Memorable Games,” for example.

After a chess player has won the world title—the one goal toward which he has presumably striven throughout his entire chess career—a certain relaxation inevitably enters into his play. The immense strain of the long cycle by which he achieved a match for the title, and the enormous output of energy required by the match itself, is bound to take its toll. This was particularly evident with Tigran Petrosian, whose results in tournament competition after winning the title were little better than mediocre.

This relaxation is also evident in Spassky's play, but not nearly to such a great extent, perhaps because Spassky was himself so relaxed to begin with. At the chessboard, Spassky appears the antithesis of everybody's idea of how a world champion ought to behave. With his legs crossed and his hands resting casually in his lap, he leans back and looks at the pieces not as if he were calculating variations but as if he were watching some exotic colony of insects go about their business — interesting enough in its way, but really having nothing at all to do with him. Such detachment — or even the ability to feign it — is an invaluable asset.

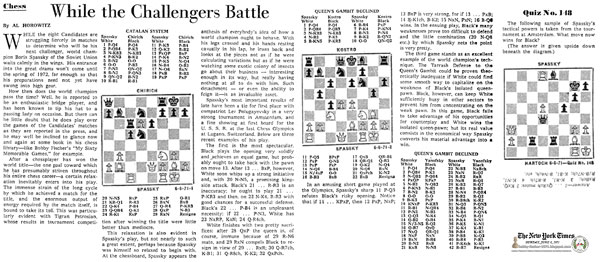

Spassky's most important results of late have been a tie for first place with compatriot Lev Polugayevsky in a very strong tournament in Amsterdam, and a fine showing at first board for the U.S.S.R. at the last Chess Olympics at Lugano, Switzerland. Below are three recent examples of his play.

The first is the most spectacular. Black plays the opening very solidly and achieves an equal game, but probably ought to take back with the pawn on move 13. After 13. … BxP, however, White soon whips up a strong initiative and, with 20. N-N5, a promising kingside attack. Black's 21. … R-R3 is an inaccuracy; he ought to play 21 … P-KR3 and then on 22. K-K4, RR-3 with good chances for a successful defense. Black's 22. … P-B4 is an unpleasant necessity; if 22. … P-N3, White has 23. NxRP, KxN; 24. Q-R4ch.

White finished with two pretty sacrifices; after 28. QxP the queen is, of course, immune because of 29. R-N6 mate, and 29. RxN compels Black to resign in view of 29. … RxR; 30. Q-R7ch, K-B1; 31. Q-R8ch, K-K2; 32. QxPch.

In an amusing short game played at the Olympics, Spassky's sharp 11. P-Q5 refutes Black's risky opening. Notice that if 11. … KPxP, then 12. PxP, NxP; 13. BxP is very strong, for if 13. … PxB; 14. B-K1ch, B-K2; 15. NxN PxN; 16. B-Q6 wins. In the ensuing play, Black's many weaknesses prove too difficult to defend and the little combination (20. N-Q6 etc.) by which Spassky nets the point is very pretty.

The third game stands as an excellent examples of the world champion's technique. The Tarrasch Defense to the Queen's Gambit could be proven theoretically inadequate if White could find some smooth way to capitalize on the weakness of Black's isolated queen-pawn. Black, however, can keep White sufficiently busy in other sectors to prevent him from concentrating on the weak pawn. In this game, Black falls to take advantage of his opportunities for counterplay and White wins the isolated queen-pawn' but its real value consists in the economical way Spassky converts his material advantage into a win.