Dayton Daily News Dayton, Ohio Thursday, October 14, 1971 - Page 11

Fischer Scornful of Red Chess Champ

Newsweek Feature Service — For nearly two decades, Robert James Fischer's world has consisted of 64 little squares, and his closest companions have been the 32 characters — the bishops, kings, queens, knights, pawns and rooks — of the game of chess.

Now, at age 28, Bobby Fischer is on the verge of reaping the rewards of those years of solitude and dedication. He is vying for a chance to meet world champion Boris Spassky of Russia next year in a match that, if Fischer wins, will finally establish him as the greatest chess player in the world.

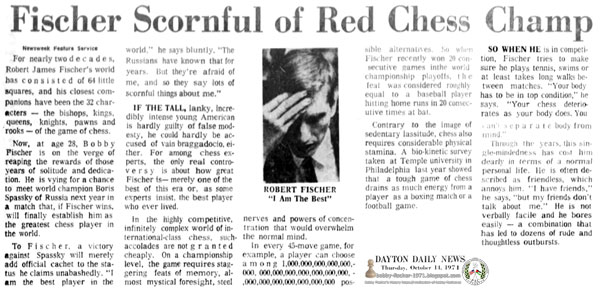

To Fischer, a victory against Spassky will merely add official cachet to the status he claims unabashedly. “I am the best player in the world,” he says bluntly. “The Russians have known that for years. But they're afraid of me, and so they say lots of scornful things about me.”

IF THE TALL, lanky incredibly intense young American is hardly guilty of false modesty, he could hardly be accused of vain braggadocio, either. For among chess experts, the only real controversy is about how great Fischer is—merely one of the best of this era or, as some experts insist, the best player who ever lived.

In this highly competitive, infinitely complex world of international-class chess, such accolades are not granted cheaply. On a championship level, the game requires staggering feats of memory, almost mystical foresight, steel nerves and powers of concentration that would overwhelm the normal mind.

In every 45-move game, for example, a player can choose among 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 possible alternatives. So when Fischer recently won 20 consecutive games in the world championship playoffs, the feat was considered roughly equal to a baseball player hitting home runs in 20 consecutive times at bat.

Contrary to the image of sedentary lassitude, chess also requires considerable physical stamina. A bio-kinetic survey taken at Temple university in Philadelphia last year showed that a tough game of chess drains as much energy from a player as a boxing match or a football game.

SO WHEN HE is in competition, Fischer tries to make sure he plays tennis, swims or at least takes long walks between matches. “Your body has to be in top condition,” he says. “Your chess deteriorates as your body does. You can't separate body from mind.”

Through the years, this single-mindedness has cost him dearly in terms of a normal personal life. He is often described as friendless, which annoys him. “I have friends,” he says, “but my friends don't talk about me.” He is not verbally facile and he bores easily — a combination that has led to dozens of rude and thoughtless outbursts.