The Indianapolis Star Indianapolis, Indiana Sunday, September 12, 1971 - Page 105

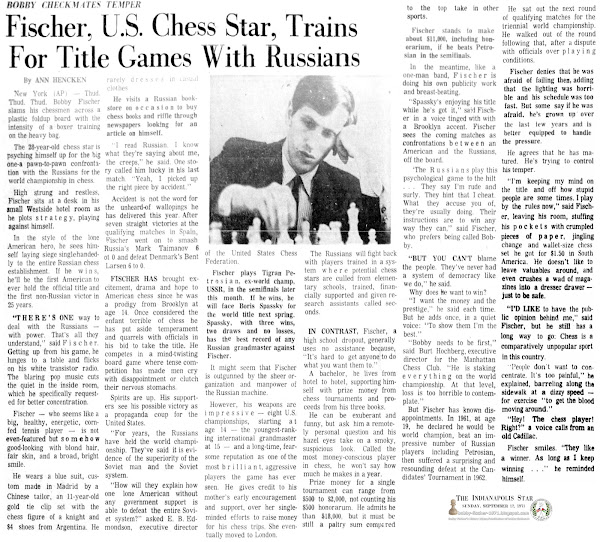

Fischer, U.S. Chess Star, Trains For Title Games With Russians by Ann Hencken

New York (AP) — Thud. Thud. Thud. Bobby Fischer slams his chessmen across a plastic fold-up board with the intensity of a boxer training on the heavy bag.

The 28-year-old chess star is psyching himself up for the big one-a pawn-to-pawn confrontation with the Russians for the world championship in chess.

High strung and restless, Fischer sits at a desk in his small Westside hotel room as he plots strategy, playing against himself.

In the style of the lone American hero, he sees himself laying siege single-handedly to the entire Russian chess establishment. If he wins, he'll be the first American to ever hold the official title and the first non-Russian victor in 25 years.

“THERE'S ONE way to deal with the Russians — with power. That's all they understand,” said Fischer. Getting up from his game, he lunges to a table and flicks on his white transistor radio. The blaring pop music cuts the quiet in the inside room, which he specifically requested for better concentration.

Fischer — who seems like a big, healthy, energetic, corn-fed tennis player — is not even-featured but somehow good looking with blond hair, fair skin, and a broad, bright smile.

He wears a blue suit, custom made in Madrid by a Chinese tailor, an 11-year-old gold tie clip set with the chess figure of a knight and $4 shoes from Argentina. He rarely dresses in casual clothes.

He visits a Russian bookstore on occasion to buy chess books and riffle through newspapers looking for an article on himself.

“I read Russian. I know what they're saying about me, the creeps,” he said. One story called him lucky in his last match. “Yeah, I picked up the right piece by accident.”

Accident is not the world for the unheard-of wallopings he has delivered this year. After seven straight victories at the qualifying matches in Spain, Fischer went on to smash Russia's Mark Taimanov 6 to 0 and defeat Denmark's Bent Larsen 6 to 0.

FISCHER HAS brought excitement, drama and hope to American chess since he was a prodigy from Brooklyn at age 14. Once considered the enfant terrible of chess be has put aside temperament and quarrels with officials in his bid to take the title. He competes in a mind-twisting board game where tense competition has made men cry with disappointment or clutch their nervous stomachs.

Spirits are up. His supporters see his possible victory as a propaganda coup for the United States.

“For years, the Russians have held the world championship. They've said it is evidence of the superiority of the Soviet man and the Soviet system.

“How will they explain how one lone American without any government support is able to defeat the entire Soviet system?” asked E.B. Edmondson, executive director of the United States Chess Federation.

Fischer plays Tigran Petrosian, ex-world champ, USSR, in the semifinals later this month. If he wins, he will face Boris Spassky for the world title next spring. Spassky, with three wins, two draws and no losses, has the best record of any Russian grandmaster against Fischer.

It might seem that Fischer is outgunned by the sheer organization and manpower of the Russian machine.

However, his weapons are impressive — eight U.S. championships, starting at age 14 — the youngest-ranking international grandmaster at 15 — and a long-time, fearsome reputation as one of the most brilliant, aggressive players the game has ever seen. He gives credit to his mother's early encouragement and support, over her single-minded efforts to raise money for his chess trips. She eventually moved to London.

The Russians will fight back with players trained in a system where potential chess stars are culled from elementary schools, trained, financially supported and given research assistants called seconds.

IN CONTRAST, Fischer, a high school dropout, generally uses no assistance because, “It's hard to get anyone to do what you want them to.”

A bachelor, he lives from hotel to hotel, supporting himself with prize money from chess tournaments and proceeds from his three books.

He can be exuberant and funny, but ask him a remotely personal question and his hazel eyes take on a smoky, suspicious look. Called the most money-conscious player in chess, he won't say how much he makes in a year.

Prize money for a single tournament can range from $500 to $2,000, not counting his $500 honorarium. He admits he makes considerably more than $18,000, but it must be still a paltry sum compared to the top take in other sports.

Fischer stands to make about $11,000 including honorarium, if he beats Petrosian in the semifinals.

In the meantime, like a one-man band, Fischer is doing his own publicity work and breast-beating.

“Spassky's enjoying his title while he's got it,” said Fischer in a voice tinged with a Brooklyn accent. Fischer sees the coming matches as confrontations between an American and the Russians, off the board.

“The Russians play this psychological game to the hilt … They say I'm rude and surly. They hint that I cheat. What they accuse you of, they're usually doing. Their instructions are to win any way they can,” said Fischer, who prefers being called Bobby.

&ldquo:BUT YOU CAN'T blame the people. They've never had a system of democracy like we do,” he said.

Why does he want to win?

“I want the money and the prestige,” he said each time. But he adds once, in a quiet voice: “To show them I'm the best.”

“Bobby needs to be first,” said Burt Hochberg, executive director for the Manhattan Chess Club. “He is staking everything on the world championship. At that level, loss is too horrible to contemplate.”

But Fischer has known disappointments. In 1961, at age 19, he declared he would be world champion, beat an impressive number of Russian players including Petrosian, then suffered a surprising and resounding defeat at the Candidates' Tournament in 1962.

He sat out the next round of qualifying matches for the triennial world championship. He walked out of the round following that, after dispute with officials over playing conditions.

Fischer denies that he was afraid of failing then, adding that the lighting was horrible and his schedule was too fast. But some say if he was afraid, he's grown up over the last few years and is better equipped to handle the pressure.

He agrees that he has matured. He's trying to control his temper.

“I'm keeping my mind on the title and off how stupid people are some times. I play by the rules now,” said Fischer, leaving his room, stuffing his pockets with crumpled pieces of paper, jingling change and wallet-size chess set he got for $1.50 in South America. He doesn't like to leave valuables around, and even crushes a wad of magazines into a dresser drawer — just to be safe.

“I'D LIKE to have the public opinion behind me,” said Fischer, but he still has a long way to go. Chess is a comparatively unpopular sport in this country.

“People don't want to concentrate. It's too painful,” he explained, barrelling along the sidewalk at a dizzy speed — for exercise “to get the blood moving around.”

“Hey! The chess player! Right?” a voice calls from an old Cadillac.

Fischer smiles. “They like a winner. As long as I keep winning …” he reminded himself.