Des Moines Tribune Des Moines, Iowa Wednesday, July 28, 1971 - Page 43

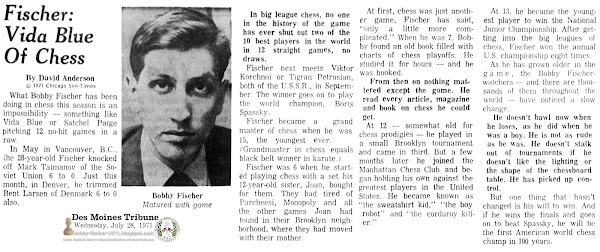

Fischer: Vida Blue of Chess by David Anderson

(Chicago Sun-Times) What Bobby Fischer has been doing in chess this season is an impossibility — something like Vida Blue or Satchel Paige pitching 12 no-hit games in a row.

In May in Vancouver, B.C., the 28-year-old Fischer knocked off Mark Taimanov of the Soviet Union 6 to 0. Just this month, in Denver, he trimmed Bent Larsen of Denmark 6 to 0 also.

In big league chess, no one in the history of the game has ever shut out two of the 10 best players in the world in 12 straight games, no draws.

Fischer next meets Viktor Korchnoi or Tigran Petrosian, both of the U.S.S.R., in September. The winner goes on to play the world champion, Boris Spassky.

Fischer became a grand master of chess when he was 15, the youngest ever.

(Grandmaster in chess equals black belt winner in karate.)

Fischer was 6 when he started playing chess with a set his 12-year-old sister, Joan, bought for them. They had tired of Parcheesi, Monopoly and all the other games Joan had found in their Brooklyn neighborhood, where they had moved with their mother.

At first, chess was just another game, Fischer has said, “only a little more complicated.” When he was 7, Bobby found an old book filled with charts of chess playoffs. He studied it for hours — and he was hooked.

From then on nothing mattered except the game. He read every article, magazine and book on chess he could get.

At 12 — somewhat old for chess prodigies — he played in a small Brooklyn tournament and came in third. But a few months later he joined the Manhattan Chess Club and began holding his own against the greatest players in the United States. He became known as “the sweatshirt kid,” “the boy robot” and “the corduroy killer.”

At 13, he became the youngest player to win the National Junior Championship. After getting into the big leagues of chess, Fischer won the annual U.S. championship eight times.

As he has grown older in the game, the Bobby Fischer-watchers — and there are thousands of them throughout the world — have noticed a slow change.

He doesn't bawl now when he loses, as he did when he was a boy. He is not as rude as he was. He doesn't stalk out of tournaments if he doesn't like the lighting or the shape of the chessboard table. He has picked up control.

But one thing that hasn't changed is his will to win. And if he wins the finals and goes on to beat Spassky, he will be the first American world chess champ in 100 years.