The Vancouver Sun Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Thursday, May 06, 1971 - Page 40

In World of Big-Time Chess Fischer's a Refreshing Pro by Bill Rayner

“It will be cheering to know that many people are skillful chess players though in many instances, their brains, in a general way, compare unfavorably with the cogitative faculties of a rabbit.”

— James Mortimer

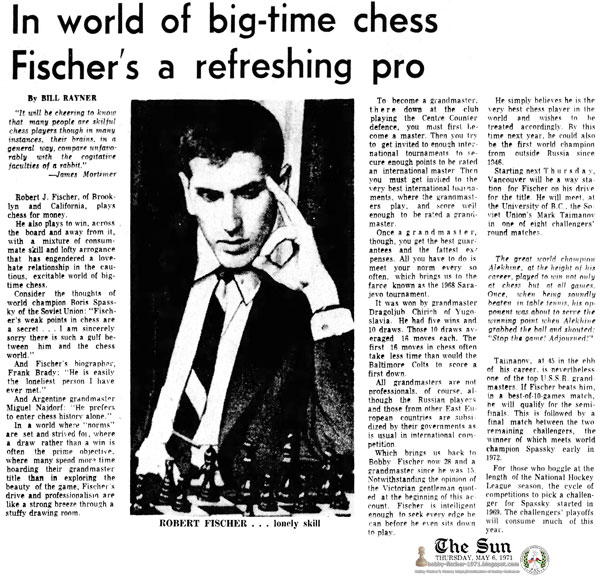

Robert J. Fischer, of Brooklyn and California, plays chess for money.

He also plays to win, across the board and away from it, with a mixture of consummate skill and lofty arrogance that has engendered a love-hate relationship in the cautious, excitable world of big-time chess.

Consider the thoughts of world champion Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union: “Fischer's weak points in chess are a secret … I am sincerely sorry there is such a gulf between him and the chess world.”

And Fischer's [unauthorized] biographer, Frank Brady: “He is easily the loneliest person I have ever met.”

And Argentine grandmaster Miquel Najdorf: “He prefers to enter chess history alone.”

In a world where “norms” are set and strived for, where a draw rather than a win is often the prime objective, where many spend more time hoarding their grandmaster title than in exploring the beauty of the game, Fischer's drive and professionalism are like a strong breeze through a stuffy drawing room.

To become a grandmaster, there down at the club playing the Centre Counter defence, you must first become a master. Then you try to get invited to enough international tournaments to secure enough points to be rated an international master. Then you must get invited to the very best international tournaments, where the grandmasters play, and score well enough to be rated a grandmaster.

Once a grandmaster, though, you get the best guarantees and the fattest expenses. All you have to do is meet your norm every so often, which brings us to the farce known as the 1968 Sarajevo tournament.

It was won by grandmaster Dragoljub Ciric of Yugoslavia. He had five wins and 10 draws. Those 10 draws averaged 16 moves each. The first 16 moves in chess often take less than would the Baltimore Colts to score a first down.

All grandmasters are not professionals, of course, although the Russian players and those from other East European countries are subsidized by their governments as is usual in international competition.

Which brings us back to Bobby Fischer now 28 and a grandmaster since he was 15. Notwithstanding the opinion of the Victorian gentleman quoted at the beginning of this account, Fischer is intelligent enough to seek every edge he can before he even sits down to play.

He simply believes he is the very best chess player in the world and wishes to be treated accordingly. By this time next year, he could also be the first world champion from outside Russia since 1946.

Starting next Thursday, Vancouver will be a way station for Fischer on his drive for the title. He will meet, at the University of B.C., the Soviet Union's Mark Taimanov in one of eight challengers' round matches.

The great world champion Alekhine, at the height of his career, played to win not only at chess but at all games. Once, when being soundly beaten in table tennis, his opponent was about to serve the winning point when Alekhine grabbed the ball and shouted: “Stop the game! Adjourned!”

Taimanov, at 45 in the ebb of his career, is nevertheless one of the top U.S.S.R. grandmasters. If Fischer beats him, in a best-of-10-game match, he will qualify for the semi-finals. This is followed by a final match between the two remaining challengers, the winner of which meets world champion Spassky early in 1972.

For those who boggle at the length of the National Hockey League season, the cycle of competitions to pick a challenger for Spassky started in 1969. The challengers' playoffs will consume much of this year.

Fischer got into the playoffs by wiping out 23 other grandmasters and international masters in the interzonal tournament at Palma de Mallorca last December. How he got into the interzonal is much more curious.

For several years now, he has boycotted the U.S. championship. Although an eight-time winner, he now refuses to play because he thinks the 11-round tournament is too short.

Fischer feels that only a fluke can prevent him from winning. A fluke is more possible in an 11-round tournament than in one of 22 rounds, so Fischer has refused to play again until the U.S. championship is made a 22-round tournament.

The U.S. Chess Federation, because of time and money problems, and because most of the other high-ranking players in the U.S. have outside jobs, have not yet given in to Fischer.

So. It happened that the 1969 U.S. tournament was also the zonal qualifying round for the world championship cycle. The top three finishers were to be seeded into the 1970 interzonal.

Because Fischer did not play, he did not qualify. The qualifiers were grandmasters Pal Benko and Sammy Reshevsky and international master William Addison. Alternate was grandmaster William Lombardy.

Suddenly, last fall, it was announced that Fischer would be one of the U.S. players at Palma de Mallorca. He replaced Benko, although all four U.S. players reportedly volunteered to step aside.

This was against International Chess Federation (FIDE) rules but the U.S. delegation managed to get the FIDE congress at Siegen, West Germany, last September to agree to the change.

Fischer, who makes more demands than a labor union, had insisted that the present challengers' matches be changed as a condition of his participation. The U.S. lost this point but Fischer agreed to play anyway.

Fischer believes that draws shouldn't count, and thinks that in a 10-round match, the first player who wins six games should be the winner.

He also is bugged by lighting (he prefers indirect fluorescent), spectators, photographers, and shiny chessmen. Once he demanded, and got, a king and queen of unequal size, the better to tell them apart.

The tournaments he plays in are stormy more often than not. He has a history of walkouts, most notably at the Olympiad in Switzerland in 1968 and the Algerian interzonal in 1967.

Fischer simply wouldn't play in the Olympiad because of conditions. At Sousse, Algeria, he forfeited three games and was finally disqualified in a dispute over the playing schedule.

At the heart of the Sousse messe, as it often is in Fischer's bouts with officialdom, was Fischer's religion. He is a member of a sect akin to the Seventh Day Adventists and will not play from sundown Fridays to sundown Saturdays and on certain other days of the year.

Because of this, Fischer found at Sousse that he had to play four Russian grandmasters on successive days. He demanded changes, and between his stubbornness and official ineptness he failed to show up for three games.

Where the Mikhail Tal-Miguel Najdorf game was adjourned during the world-U.S.S.R. match the Russians gathered in a room to analyze Tal's position as black. Eventually Boris Spassky found the winning move for white. Up jumped a man from behind and kissed Spassky enthusiastically. It was Najdorf. He won in a few moves when play resumed the next day.

Fortified apparently with a new maturity, Fischer enjoyed perhaps his greatest year in 1970. After 18 months of solitude he made a brilliant return to the battlefield in the World-U.S.S.R. match in Belgrade last April.

In this match, first of its kind, 10 Soviet Union grandmasters played four games against 10 grandmasters from the rest of the world. Playing second board for the world, Fischer buried ex-champion Tigran Petrosian with two wins and two draws.

It was at Belgrade that a hint of a new Fischer emerged away from the game. He had been expected to play first board, but Danish grandmaster Bent Larsen claimed this was his own right because he had been more active recently than Fischer.

Fischer, surprisingly agreed, saying that with his long layoff he could do a better job against Petrosian than against Spassky on the first board.

After Belgrade, Fischer went on to first-place finishes against strong fields at Zagreb, Yugoslavia, Buenos Aires and Palma de Mallorca. He faltered once, losing his game to Spassky in the 1970 Olympiad at Siegen.

While the U.S.S.R., with Spassky leading the way, retained its Olympiad title with ease, 1970 was a year of shick for the Russian chess monolith.

They had expected to win the match against the world with ease, but only scraped by, 20½-19½ (wins count one point, draws one-half point).

Even more ominous, the score on the top four boards was 10½-5½ for the world: Larsen over Spassky and alternate Leonid Stein 2½-1½; Fischer over Petrosian, 3-1; Hungary's Lajos Portisch over Viktor Korchnoi, 2½-1½, and Czechoslovakia's Vlastimil Hort over Lev Polugaevsky, 2½-1½.

Then, in the interzonal, only two of the four Russians entered qualified for the challengers' round. While Fischer led with 18½-4½, Taimanov squeezed into the last qualifying position with a 14-9 record and Yefim Geller was just ahead with 15-8.

The Russians are also getting old. At Belgrade, the average age of the U.S.S.R. team was 43, compared with 38.7 for the world team — and this included the 60-year-old Najdorf.

And in the present challengers' round, the four non-Russians average just over 30, while the four Russians average 42-plus.

Fischer's 17-year age advantage over Taimanov is a sizable factor in the the pair's match here, but the Russian musician-grandmaster remains optimistic.

Botvinnik, one of the long string of Russian world champions, perfected his preparation for tournament play by having a colleague blow cigarette smoke in his face during training games.

Although this is the first time he has been a challenger in 18 years, Taimanov has been playing well in recent tournaments. He plays the game with gusto and believes there is no such thing as an indefensible position.

Taimanov is faulted, however, for underestimating opponents' resources and for superficial play in difficult positions.

Superficial is not the name for Fischer's game. He scorns draws and plays until the last possibility for a win is exhausted. This drive brings many wins, but also the occasional loss through taking unwarranted risks, and fatigue.

Constant striving for the initiative and the utmost accuracy in the employment of time are two of Fischer's big weapons. He also has the ability to note the smallest error by his opponent.

Fischer is considered the greatest expert today in the Ruy Lopez, the classic P-K4 opening. In fact, he long ago settled on P-K4 as the only opening move worth considering, and until recently played it almost exclusively when he had the white pieces.

As black he leans toward the Najdorf Sicilian and the Grunfeld defences, with the Benoni his favorite against P-Q4.

However, just to confuse everything, Fischer tried the English opening (P-QB4) and P-QN3 twice with white at the interzonal. He also employed the rarely used Alekhine defense three times as black, although admittedly against weaker opponents.

So he has come to play, has Robert J. Fischer, out there at UBC's graduate center. In a private room, of course, while spectators watch a demonstration board elsewhere.

And we trust the lighting and everything else will be satisfactory, for a Fischer usually passes this way only once.

“Is it against the law to kill a reporter?”

— R.J. Fischer

Belgrade, 1970.