The San Francisco Examiner San Francisco, California Sunday, October 03, 1971 - Page 160

Will an American Win the World Chess Crown? by George Koltanowski

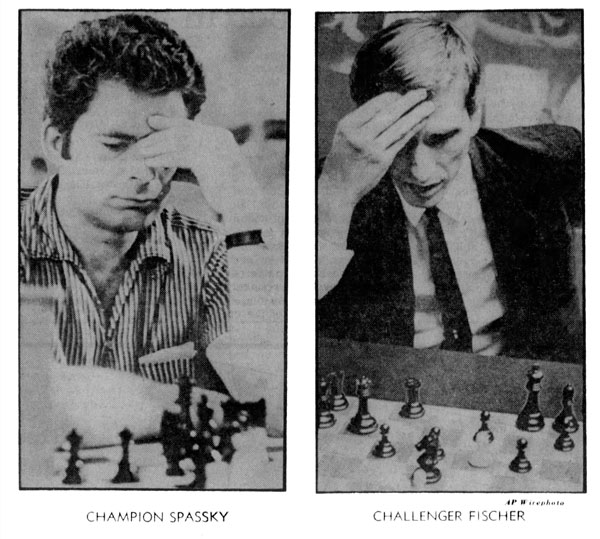

Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown. In the realm of chess, this particular head is that of Russia's Boris Spassky, Chess Champion of the World. For hardly had he been crowned three years ago than claimants to the throne began clamoring at its foot. By last week, as the finals of the Candidates' matches got underway in Buenos Aires, virtually all the claimants had been pushed aside and the field of challengers had been whittled down to two. One was Tigran Petrosian, another Russian and another World Champion (from 1963 to 1969). The other was Robert Fischer, the brilliant New Yorker. Five times in the past, Fischer has started the long trek to the top. Four times he has either been beaten or has found reasons to abandon the fight.

This year Bobby has every chance to go all the way. His performance in the quarter finals and semi-finals of the Candidates matches is absolutely unprecedented. First, in Vancouver, he shellacked Russia's Mark Taimanov, one of the world's best players, 6-0. Then in Denver, he came up against Bent Larsen, the cheerful and optimistic Dane who, in Mallorca in 1970, beat Fischer and told me confidently: “I will be the one who will play Spassky for the title.” What happened? The incredible Bobby smashed Larsen, again in six straight games, causing a Copenhagen chess wrote to observe: “It has been a sad, sad spring for Denmark.”

‘Six To Nothing’ — What made for sadness in Denmark — and elation in the U.S. — made for pronounced nervousness in Russia, where the World Champion's crown has been located, on one head or another, for the past quarter century. There was graphic evidence of this in the Moscow offices of Izvestia. Immediately after the Fischer-Larsen match ended but before the results had been published or broadcast in Russia, the telephones at Izvestia began jumping. “Six to nothing,” the telephone girls kept saying without waiting for the question, “six to nothing,” “six to nothing.”

Spassky's later performance at the Canadian Open in Vancouver (Fischer did not play there) did little to reassure his countryman. He won — but barely.

A survey of Western masters last week indicated a nearly unanimous opinion that Fischer would win in Buenos Aires and go on to beat Spassky. The sole dissenter was, of all people, the now melancholy Dane, Bent Larsen.

Bobby Fischer is, indeed, unique. He became U.S. champion at the age of 14 back in 1957, and won that title thereafter every time he tried to, eight in all.

He has something akin to a fixation about lighting. In Denver, he tried six different kinds of light fixtures before he found one that satisfied his demanding eyes. He also insists on cathedral-like silence. Spectators have to sit back at least six rows from the playing area. If someone makes a noise or, worse, takes a picture of him during play, he will erupt, buttonhole an official and insist that the offender be ousted from the hall.

Signals of Doom — When the lighting is to his fancy and the spectators are behaving themselves, Fischer is glued to his chair. Most of the time he hunches over the board, his head in his hands, a picture of quiet thinking power. If you know him, you can tell when he is winning. His eyes now glance from the board to his opponent or to the wall board where the game is being duplicated for the public. When that happens, his opponent is doomed.

What of Petrosian, the Armenian who is the sole roadblock (except possibly Fischer's own temperament) to a Fischer-Spassky World Championship match? He is 42, and an extremely cool and gentlemanly player. Perhaps because he is partially deaf, he seems impervious to spectator distraction. He and Fischer have played against each other before, each having won three games from the other, but two of Fischer's wins occurred in 1970, the last time they met, in a four-game match, the other two games being draws.

In Buenos Aires, the winner will have to score 6½ points (one point for a win, one half point for a draw). If the contestants are tied after 12 games, four more will be played, and if the score is still tied, the match will be decided by the flip of a coin.

A Changed Attitude — As the ringing telephones in Izvestia indicated, Russian chess now takes Bobby Fischer seriously. A recently printed article in Komsomolskaja Pravda reported; “ For many of our players, Fischer has remained a small boy whom they have beaten so often. But the small boy, who used to cry after every defeat, has turned into a real fighter, who commands an arsenal of modern chess weapons which nobody can ignore.”

That arsenal is now being brought into play half a world away from Russia, the besieged stronghold of chess.