New York Times, New York, New York, Sunday, November 14, 1971 - Page 233

Chess: Fischer Never Fails To Astound by Al Horowitz

In a way, it is much easier to write retrospectively of Bobby Fischer's 5½-2½ triumph over former world champion Tigran Petrosian than it was to write of his consecutive 6-0 victories against Soviet grandmaster Mark Taimanov, or his Danish semi-final opponent Bent Larsen. After the Taimanov match, everybody was simply astounded that one of the candidates to challenge the world champion could beat another so decisively. After he did the same to Larsen, however, it began to appear as if Fischer's opponents were like the poor knights in some fairy-tale who, arriving sometime before the hero, ride out to slay the dragon and are devoured instead.

Petrosian, however, scored 2½ points. While that doesn't exactly make him St. George, he was no mere dragon-fodder either, and so one can write about his defeat not as if it were a fairy-tale, but as if it were a chess match; it becomes somehow meaningful again to say that the better player won.

At the beginning, though, it was well-nigh irresistible to look on Petrosian as a mere mortal setting out to do battle against a somewhat superhuman foe. How else explain the spontaneous outburst of the audience, the impassioned cries of “Tigran! Tigran!” that greeted the ex-world champ after he won the second game? Fischer, it is reported, was suffering from a cold that was, during that game, so severe that he could hardly see the board.

Now a cold is a pretty good sign of human fallibility, all things considered. Even more so was Fischer's decision‐as bad an error as leaving one's queen en prise, and as costly — to play when he was physically indisposed: he did have a right to postpone the game. It is almost as if he refused to admit that he is human after all.

After the disaster of the second game, Fischer looked very mortal indeed. He was also lost in the third game, but somehow managed to draw. After the fourth and fifth games also resulted in draws, it began to look as if Petrosian was applying, successfully, the same squeeze tactics with which he had vanquished his two previous opponents: he would, by relying on better nerves and greater staying power, wear Fischer down until he collapsed under the strain. But by the sixth game Fischer's cold was better and soon it was Petrosian's turn to be sick.

Petrosian, in an interview he gave sometime before the match, reportedly remarked that he did not think Fischer's play of sufficiently high caliber to rank him among the top grandmasters and that if Bobby somehow got past him, he would lay 5-1 odds on world champion Spassky when Fischer came to play for the title. Now Petrosian is not a stupid man, and there is no use mailing bets to him care of the Russian embassy; he was simply striking a shrewd psychological blow that did, indeed, have some of the effect he desired; Fischer was infuriated.

Unfortunately for Petrosian's calculations, however, he was infuriated not to rashness, but to greater and greater accuracy, and thus won the last four games of the match in a way that conveys the impression that he is off on a new streak of victories that may well break his old record. Whether world champion Boris Spassky is suited to the role of St. George, only time will tell.

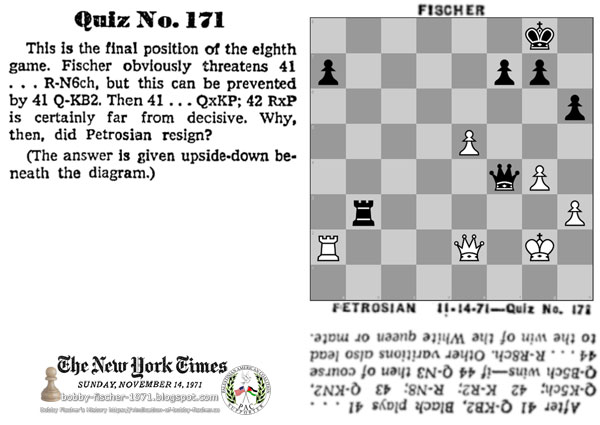

Quiz No. 171. This is the final position of the eighth game. Fischer obviously threatens 41. … R-N5ch, but this can be prevented by 41. Q-KB2. Then 41. … QxKP; 42. RxP is certainly far from decisive. Why, then, did Petrosian resign? (The answer is given upside-down beneath the diagram.)

After 41. Q-KB2, Black plays 41. … Q-K5ch; 42. K-R2 R-N8; 43. Q-KN2 Q-B5ch wins—if 44. Q-N3 then of course 44. … R-R8ch. Other variations also lead to the win of the White queen or mate.