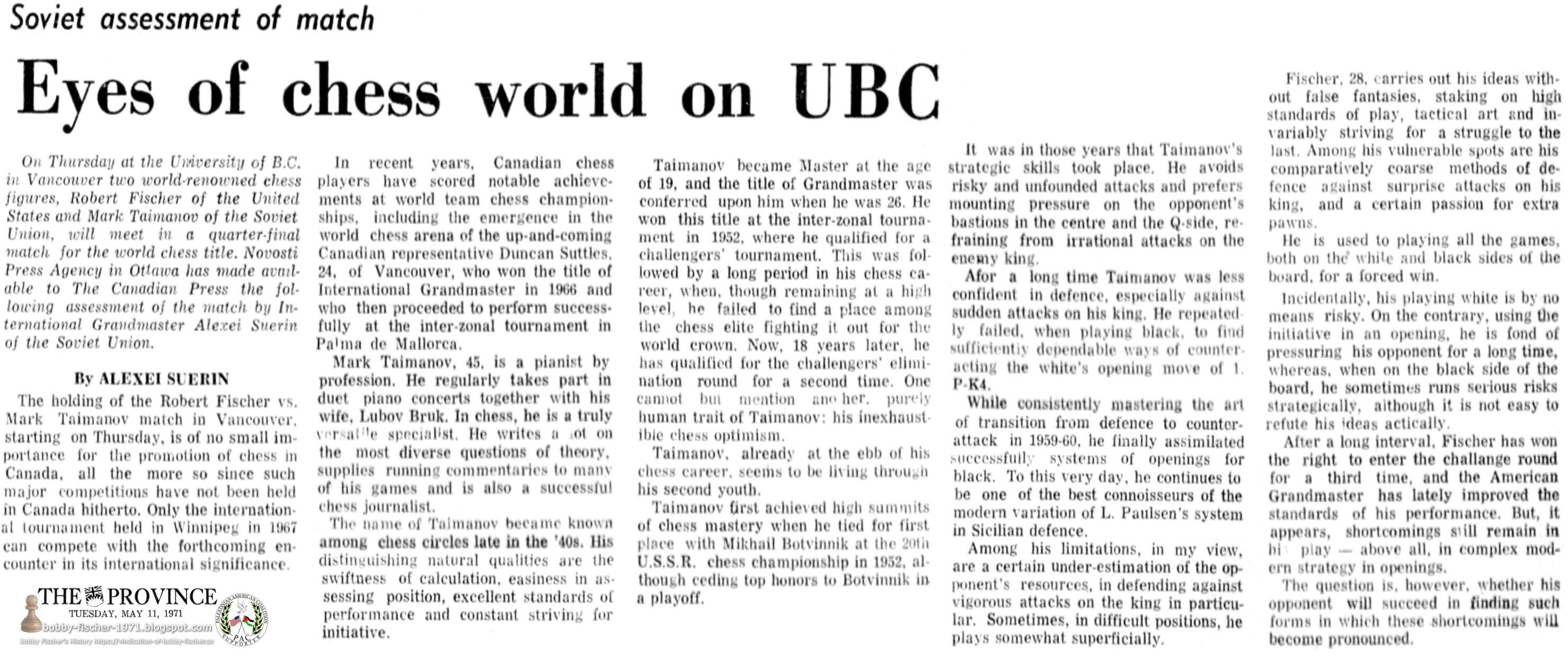

The Province Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Tuesday, May 11, 1971 - Page 25

Soviet Assessment of Match - Eyes of Chess World on UBC

On Thursday at the University of B.C. in Vancouver two world-renowned chess figures, Robert Fischer of the United States and Mark Taimanov of the Soviet Union, will meet in a quarter-final match for the world chess title. Novosti Press Agency in Ottawa has made available to The Canadian Press the following assessment of the match by International Grandmaster Alexei Suetin of the Soviet Union. by Alexei Suetin

The holding of the Robert Fischer vs. Mark Taimanov match in Vancouver, starting on Thursday, is of no small importance for the promotion of chess in Canada, all the more so since such major competitions have not been held in Canada hitherto. Only the international tournament held in Winnipeg in 1967 can compete with the forthcoming encounter in its international significance.

In recent years, Canadian chess players have scored notable achievements at world team chess championships, including the emergence in the world chess arena of the up-and-coming Canadian representative Duncan Suttles, 24, of Vancouver, who won the title of International Grandmaster in 1966 and who then proceeded to perform successfully at the interzonal tournament in Palma de Mallorca.

Mark Taimanov, 45, is a pianist by profession. He regularly takes part in duet piano concerts together with his wife, Lubov Bruk. In chess, he is truly versatile specialist. He writes a lot on the most diverse questions of theory, supplies running commentaries to many of his games and is also a successful chess journalist.

The name of Taimanov became known among chess circles late in the '40s. His distinguishing natural qualities are the swiftness of calculation, easiness in assessing position, excellent standards of performance and constant striving for initiative.

Taimanov became Master at the age of 19, and the title of Grandmaster was conferred upon him when he was 26. He won this title at the interzonal tournament in 1952, where he qualified for a challengers' tournament. This was followed by a long period in his chess career, when, though remaining at a high level, he failed to find a place among the chess elite fighting it out for the world crown. Now, 18 years later, he has qualified for the challengers' elimination round for a second time. One cannot but mention another, purely human trait of Taimanov: his inexhaustible chess optimism.

Taimanov, already at the ebb of his chess career, seems to be living through his second youth.

Taimanov first achieved high summits of chess mastery when he tied for first place with Mikhail Botvinnik at the 20th U.S.S.R. chess championship in 1952, although ceding top honors to Botvinnik in a playoff.

It was in those years that Taimanov's strategic skills took place. He avoids risky and unfounded attacks and prefers mounting pressure on the opponent's bastions in the center and the Q-side, refraining from irrational attacks on the enemy king.

For a long time Taimanov was less confident in defense, especially against sudden attacks on his king. He repeatedly failed, when playing black, to find sufficiently dependable ways of counteracting the white's opening move of 1. P-K4.

While consistently mastering the art of transition from defense to counterattack in 1959-60, he finally assimilated successfully systems of openings for black. To this very day, he continues to be one of the best connoisseurs of the modern variation of L. Paulsen's system in Sicilian defense.

Among his limitations, in my view, are a certain under-estimation of the opponent's resources, in defending against vigorous attacks on the king in particular. Sometimes, in difficult positions, he plays somewhat superficially.

Fischer, 28, carries out his ideas without false fantasies, staking on high standards of play, tactical art and invariably striving for a struggle to the last. Among his vulnerable spots are his comparatively coarse methods of defense against surprise attacks on his king, and a certain passion for extra pawns.

He is used to playing all the games, both on the white and black sides of the board, for a forced win.

Incidentally, his playing white is by no means risky. On the contrary, using the initiative in an opening, he is fond of pressuring his opponent for a long time, whereas, when on the black side of the board, he sometimes runs serious risks strategically, although it is not easy to refute his ideas tactically.

After a long interval, Fischer has won the right to enter the challenge round for a third time, and the American Grandmaster has lately improved the standards of his performance. But, it appears, shortcomings still remain in his play — above all, in complex modern strategy in openings.

The question is, however, whether his opponent will succeed in finding such forms in which these shortcomings will become pronounced.